You wake up and immediately face your first decision: snooze or get up? Then it’s coffee or tea, shower first or breakfast, which shirt goes with these pants, should you pack lunch or buy it, take the highway or side streets, respond to that text now or later. And it’s not even 8 AM.

By the time most people start their “real” work, they’ve already made dozens of decisions. Each one seems trivial in isolation, but together they create an invisible tax on your mental energy. This is decision fatigue—the deteriorating quality of decisions made after a long session of decision-making. But here’s what the research doesn’t capture: for many of us, that “long session” starts the moment we open our eyes.

The productivity world loves to talk about decision fatigue as if it’s a simple scheduling problem. “Just batch your decisions!” they chirp. “Wear the same thing every day like Steve Jobs!” But this advice misses the deeper issue. Decision fatigue isn’t just about having too many choices—it’s about living in a world designed to extract decisions from you constantly, then wondering why you’re exhausted.

The Hidden Weight of Micro-Choices

Decision fatigue shows up in ways we rarely connect to the actual decisions. You find yourself scrolling mindlessly through your phone instead of tackling that important project. You snap at your partner over something small. You order takeout again instead of cooking the groceries you bought with good intentions. These aren’t character flaws—they’re symptoms of a depleted decision-making system seeking the path of least resistance.

The cruel irony is that the decisions that drain us most aren’t the big, meaningful ones. Those we actually prepare for. It’s the endless stream of micro-choices that nobody warns you about. Should you respond to that email now or after lunch? Which brand of pasta sauce? Do you need to stop for gas today or can it wait? Paper or plastic? Each decision is a tiny withdrawal from your cognitive bank account.

Research shows that judges make harsher parole decisions right before lunch when their decision-making reserves are low. If trained professionals can’t escape this pattern, what hope do the rest of us have when we’re deciding between seventeen different streaming options after a day of constant choices?

Every decision you don’t have to make is energy you can spend on something that actually matters.

The modern world has multiplied our decision points exponentially. Our grandparents might have had three TV channels and one grocery store. We have infinite entertainment options and aisles of nearly identical products, each demanding we weigh options we don’t actually care about. The abundance that was supposed to improve our lives often just increases our cognitive overhead.

When Options Become Obstacles

There’s a reason why restaurants with massive menus often leave you feeling overwhelmed rather than excited. More options don’t equal better outcomes—they equal more work for your brain. Every additional choice point requires you to evaluate, compare, and commit. Even when the stakes are low, the cognitive cost is real.

Ambiguity makes this worse. When expectations aren’t clear, your brain has to fill in the gaps, running scenarios and contingencies in the background. “Should I dress up for this meeting or is it casual?” becomes a multi-variable equation involving company culture, who else will be there, and what impression you want to make. A simple clothing choice becomes a strategic decision requiring mental energy you might need elsewhere.

This is why some of the most successful people seem almost boring in their personal habits. They’re not lacking creativity—they’re protecting it. When you don’t have to decide what to eat for breakfast or which gym to go to, you preserve decision-making capacity for choices that actually move your life forward.

The Fatigue Escape Routes

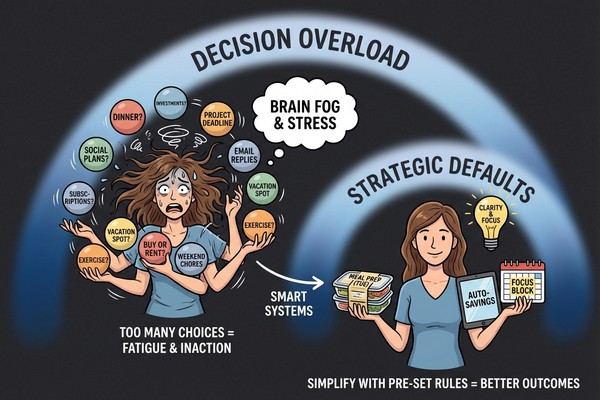

When your decision-making system gets overloaded, it doesn’t just stop working—it starts taking shortcuts. Usually bad ones. You might recognize these patterns.

You scroll instead of choosing. Faced with too many options, you defer the decision by mindlessly browsing social media or news feeds. You snap at small things. Minor irritations become major reactions because you don’t have the mental bandwidth to regulate your response. You experience avoidance paralysis. Important decisions get pushed off indefinitely because making any choice feels overwhelming. Or you default to “no.” You start declining invitations and opportunities not because you don’t want them, but because saying yes requires more decision-making energy than you have.

These aren’t personal failings. They’re predictable responses to cognitive overload. Your brain is doing exactly what it’s designed to do—conserve energy when resources are scarce.

The Power of Strategic Defaults

Here’s where most productivity advice gets it backwards. Instead of trying to make better decisions, the goal should be to make fewer decisions. This isn’t about being rigid or uncreative—it’s about being intentional with your mental energy.

A default isn’t a limitation—it’s a liberation. When you decide once instead of deciding repeatedly, you free up cognitive space for choices that actually deserve your attention. The key is identifying which decisions are worth your energy and which are just energy drains disguised as options.

Think about the decisions you make most often. Many of them probably fall into predictable categories: what to eat, what to wear, which route to take, how to spend your evening, which products to buy. These recurring choices are perfect candidates for default solutions.

Where Defaults Work Best

Morning routines: Instead of deciding what to do each morning, create a sequence you follow automatically. Same wake time, same breakfast, same order of activities. This isn’t about being robotic—it’s about starting your day without depleting your decision-making reserves before you even leave the house.

Wardrobe systems: You don’t need to wear identical outfits, but having a consistent style framework eliminates daily clothing decisions. Maybe it’s always dark jeans with a rotation of three shirt colors. Maybe it’s the same dress style in different patterns. The specifics matter less than the consistency.

Meal planning: Deciding what to eat three times a day, every day, is exhausting. Having default breakfast options, go-to lunch choices, and a rotation of dinner meals you actually enjoy removes hundreds of food decisions from your week.

Financial choices: Automatic savings, bill pay, and investment contributions eliminate recurring money decisions. When your financial system runs on autopilot, you’re not constantly deciding whether to save this month or which bills to prioritize.

The goal isn’t to eliminate all choices—it’s to eliminate the choices that don’t matter so you can focus on the ones that do.

The beauty of defaults is that they’re not permanent. You can always override them when you want something different. But having a fallback option means you’re choosing to deviate rather than being forced to choose from scratch every time.

Your Three-Decision Challenge

Here’s a practical starting point: identify three recurring decisions that drain your energy and create defaults for them this week. Maybe it’s what to have for breakfast, choosing one or two options you’ll rotate. Maybe it’s which podcast to listen to during your commute, picking a daily show you enjoy. Or maybe it’s how to spend the first hour after work, whether that’s reading, walking, or another specific activity.

Start small. The goal isn’t to automate your entire life—it’s to experience what it feels like to have more decision-making energy available for things that actually matter to you.

Beyond Personal Defaults

Individual defaults help, but they’re just the beginning. The real opportunity lies in systems that can propose and remember defaults for you. Imagine having support that learns your preferences and suggests options based on your actual patterns, not generic recommendations.

This is where technology could actually reduce mental load instead of adding to it. Instead of giving you more options to evaluate, the right system would learn that you prefer quick lunches on Tuesdays, that you’re more likely to exercise in the morning, that you need reminders about recurring tasks before they become urgent.

The future of mental load reduction isn’t about making better decisions—it’s about making fewer of them. When the small stuff runs on autopilot, you finally have space to think about the big stuff. And maybe, just maybe, you’ll have energy left over for the spontaneous moments that make life interesting.

Decision fatigue isn’t a personal weakness—it’s a design problem with modern life. The solution isn’t willpower. It’s wisdom about where to spend your mental energy and where to let defaults carry the load.

This article was created with collaboration between humans and AI—we hope you ❤️ it.