There’s a woman in your office who never seems flustered. Her desk is pristine, her emails are crisp, and she glides from meeting to meeting with an enviable calm. You might admire her—or secretly resent her—but what you probably don’t see is the 6 AM prep session, the triple-checked notes hidden in her laptop, or the way she rehearses casual responses to predictable questions.

This is competence theater: the exhausting performance of looking like you have everything under control. It’s different from actually being competent. It’s the extra layer of work we do to appear effortless, and it’s quietly draining people everywhere.

The performance starts early and runs late. It’s the parent who preps elaborate snacks for the school event while texting “Oh, just threw this together!” It’s the manager who spends an hour crafting a “quick update” email that sounds breezy and confident. It’s the entrepreneur who presents polished slides while frantically googling industry terms five minutes before the pitch.

We’re not just doing the work—we’re doing the work of making the work look easy.

The Hidden Choreography of Looking Effortless

At work, competence theater shows up in a thousand small performances. You smooth over the fact that you had to ask three people for clarification before understanding the brief. You delete the draft emails that revealed your uncertainty. You nod knowingly in meetings about processes you’re still figuring out, then frantically research later.

The theater extends to our tools and systems too. We hide our messy note-taking apps behind clean presentations. We use complex project management systems not because they help us think, but because they look professional to others. We create elaborate organizational schemes that photograph well for social media but crumble under real use.

At home, the performance is even more elaborate. The house that looks “naturally” tidy required an hour of strategic cleaning before guests arrived. The family dinner that appears effortlessly nourishing involved meal planning, grocery coordination, and backup options for picky eaters. The birthday party that seemed “so fun and relaxed” was choreographed down to the backup activities and dietary accommodations.

Social media amplifies this theater exponentially. We curate not just our successes, but our struggles too—sharing only the photogenic kinds of chaos, the relatable-but-not-too-messy moments. Even our vulnerability becomes performance.

The Gendered Weight of Appearing Effortless

Women carry a disproportionate burden in this performance, expected to make complex coordination look natural and intuitive. The working mother who “manages it all” is praised, but the infrastructure that makes it possible—the lists, the backup plans, the emotional labor of anticipating everyone’s needs—remains invisible.

There’s a particularly cruel expectation that women should make competence look innate rather than learned. A man who admits to using systems and tools is seen as strategic. A woman doing the same might be viewed as over-organized or anxious. So women learn to hide their scaffolding, pretending that remembering everyone’s schedules and preferences just comes naturally.

This creates a vicious cycle. When women make their competence look effortless, other women feel inadequate by comparison. The hidden work stays hidden, and the standards for “natural” capability keep rising.

The stakes feel higher for women in professional settings too. Research shows that women are judged more harshly for visible uncertainty or preparation. A man who says “let me check my notes” appears thorough. A woman doing the same might seem unprepared. So women over-prepare, then hide the preparation, creating double the work for the same perceived competence.

The Overhead of Perfection

Competence theater requires enormous overhead—the meta-work of managing how your work appears to others. This overhead compounds in ways that aren’t immediately obvious.

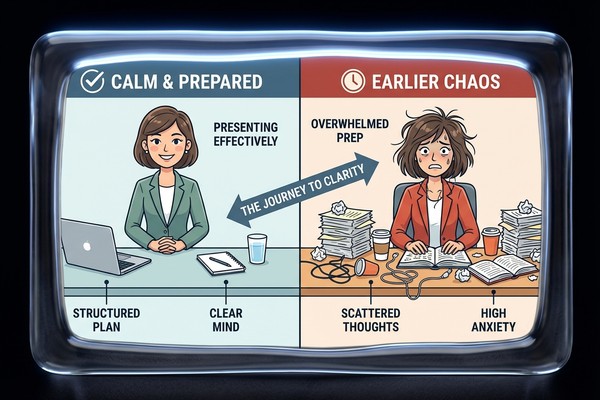

First, there’s the preparation overhead. You don’t just prepare for the meeting; you prepare to look like you didn’t over-prepare for the meeting. You practice sounding casual about information you researched extensively. You memorize key points so you won’t need to reference notes that might make you look less authoritative.

Then there’s the polishing overhead. Every output gets an extra pass to remove traces of the messy thinking process. Emails are rewritten to sound more confident. Presentations are scrubbed clean of the exploratory questions that led to insights. The work product loses the texture of actual human thinking.

The most exhausting part isn’t being competent—it’s looking like competence comes naturally.

There’s also emotional overhead. You’re not just managing your actual stress about deadlines and outcomes; you’re managing how your stress appears to others. You learn to modulate your voice in status updates, to frame setbacks as learning opportunities, to appear appropriately concerned but not overwhelmed.

The rechecking overhead might be the most insidious. When you can’t appear to need verification, you verify everything multiple times privately. You double-check information you’re confident about, just in case. You create backup plans for your backup plans, because asking for help mid-crisis would break the illusion of effortless competence.

The Isolation of Self-Reliance

Perhaps the cruelest aspect of competence theater is how it prevents us from accessing the support we actually need. When you’ve invested in appearing self-sufficient, asking for help feels like admitting fraud.

This isolation compounds over time. The more successfully you perform competence, the less likely people are to offer help. They assume you don’t need it. Meanwhile, you’re drowning behind a facade of capability, unable to signal distress without dismantling your entire professional persona.

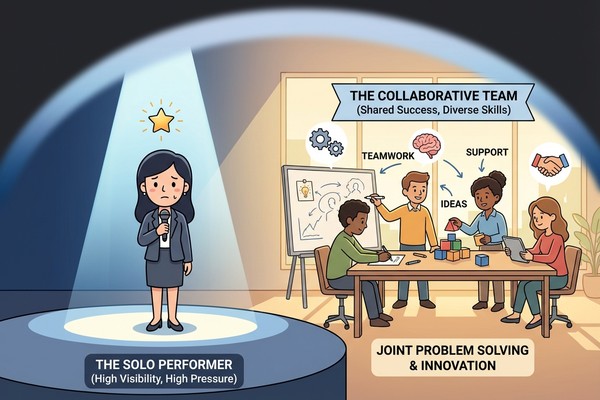

The theater also prevents us from building the collaborative relationships that make work sustainable. When everyone is performing individual competence, we miss opportunities for shared systems, collective problem-solving, and mutual support. Teams become collections of isolated performers rather than integrated units.

Even worse, competence theater trains us to distrust our own need for support. We internalize the performance, believing that truly competent people shouldn’t need the scaffolding we rely on. We start to see our systems and tools as crutches rather than intelligent adaptations.

Redefining Competence as Building Support

Real competence isn’t about appearing to need nothing—it’s about building sustainable systems for getting things done. This includes acknowledging what you don’t know, creating reliable ways to track information, and developing relationships that provide backup when you need it.

The most competent people aren’t those who never struggle; they’re those who struggle efficiently. They ask clarifying questions early rather than guessing. They build systems that catch their mistakes. They delegate not because they’re lazy, but because they understand their own limitations.

True competence means being honest about your capacity and building accordingly. It means using tools that help you think, even if they’re not aesthetically pleasing. It means asking for help before you’re desperate, and offering help before you’re asked.

This reframe is liberating but requires courage. It means letting people see your notes, your questions, your process. It means admitting when you’re confused and celebrating when you figure things out. It means treating competence as a practice rather than a performance.

Competence isn’t about having no needs—it’s about meeting your needs intelligently.

Where Are You Performing Instead of Being Supported?

The hardest part of recognizing competence theater is how normalized it’s become. We’ve been performing for so long that the performance feels like authenticity. But there are telling signs.

Notice where you feel pressure to appear more knowledgeable than you are. Where do you nod along in conversations, planning to research later rather than asking questions now? Where do you create elaborate workarounds to avoid appearing uncertain?

Pay attention to the tools and systems you hide. What organizational methods do you use privately but wouldn’t want colleagues to see? What notes do you take that you’d be embarrassed to share? These hidden supports often represent your most honest relationship with your own thinking process.

Consider the help you don’t ask for. What tasks do you struggle with repeatedly rather than seeking guidance? Where do you reinvent solutions instead of learning from others? What support would you want if you could access it without judgment?

Look at your preparation rituals too. Where do you over-prepare not because the situation demands it, but because you need to appear naturally informed? What would change if you could be honest about your preparation process?

The goal isn’t to abandon all professional presentation, but to distinguish between helpful preparation and exhausting performance. Some polish serves genuine communication purposes. But much of what we do is theater—and recognizing it is the first step toward something more sustainable.

The future belongs to tools and cultures that make support normal rather than shameful. Instead of hiding our scaffolding, we can build better scaffolding together. Instead of performing effortless competence, we can practice supported competence—and maybe, finally, get some rest.

This article was created with collaboration between humans and AI—we hope you ❤️ it.