You know that feeling when you confidently tell someone “I’ll have this done by Thursday,” and then Thursday arrives like an unwelcome surprise guest while you’re still knee-deep in Tuesday’s work? You’re not lazy. You’re not disorganized. You’re human, and you’ve just encountered one of psychology’s most persistent phenomena: the planning fallacy.

Last week, I watched a friend—a brilliant project manager who orchestrates million-dollar initiatives—estimate that organizing her daughter’s birthday party would take “maybe two hours, tops.” Four hours later, she was still untangling the logistics of dietary restrictions, coordinating with other parents, and realizing the bounce house company needed a different insurance form. “I don’t understand,” she said, genuinely puzzled. “I plan complex projects for a living.”

The planning fallacy isn’t about incompetence. It’s about the beautiful, terrible way our brains work. We consistently underestimate how long tasks will take, not because we’re careless, but because we’re optimists trapped in our own mental models.

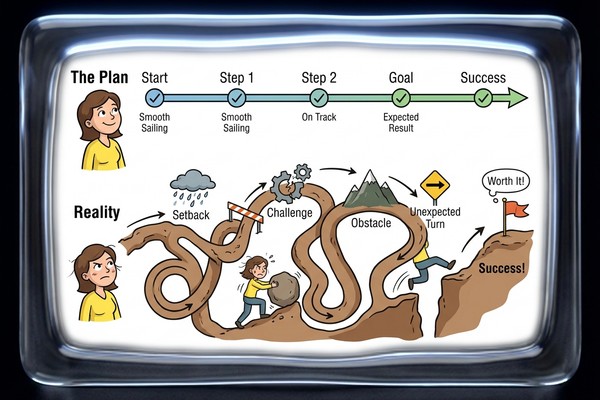

The Clean Timeline Illusion

When we plan, we imagine the best-case scenario. We picture ourselves moving smoothly from Point A to Point B, uninterrupted and focused. In our minds, we’re the protagonist of a productivity documentary where everything flows seamlessly.

But real life doesn’t happen in clean timelines. Real life happens in a world where the printer runs out of toner, your toddler decides Tuesday is the perfect day for an existential crisis, and that “quick” email check turns into forty-five minutes of inbox archaeology. We plan for the task, but we forget to plan for life happening around the task.

The research on planning fallacy is both fascinating and depressing. Even when people are explicitly asked to consider what could go wrong, they still underestimate completion times. Even when they’re reminded of past projects that ran long, they maintain unrealistic optimism about the current one. Our brains are wired to believe this time will be different.

We don’t just underestimate time—we underestimate the complexity of being human while working.

This isn’t a bug in our thinking; it’s a feature. Optimism helps us start projects that might otherwise feel overwhelming. But it becomes a problem when our planning consistently sets us up for the stress of running behind, the guilt of missing deadlines, and the exhaustion of constantly playing catch-up.

The Hidden Time Tax of Mental Load

Here’s what makes planning particularly treacherous for working parents and anyone carrying significant mental load: the invisible time costs that never make it onto our calendars.

When you estimate that grocery shopping will take an hour, you’re probably calculating drive time, shopping time, and checkout time. But you’re not accounting for the ten minutes spent searching for the list you made, the detour because you forgot your reusable bags, the extra fifteen minutes because your usual brand was out of stock and you had to research alternatives on your phone, or the unexpected conversation with a neighbor in the parking lot.

These aren’t interruptions—they’re the texture of real life. But our planning minds edit them out like a highlight reel, leaving only the main event.

For people managing households, this phenomenon is particularly cruel. You might allocate thirty minutes to “get the kids ready for school,” but that doesn’t include the time spent looking for the missing shoe, negotiating the outfit crisis, or dealing with the sudden announcement that today is actually pajama day and everyone needs to start over.

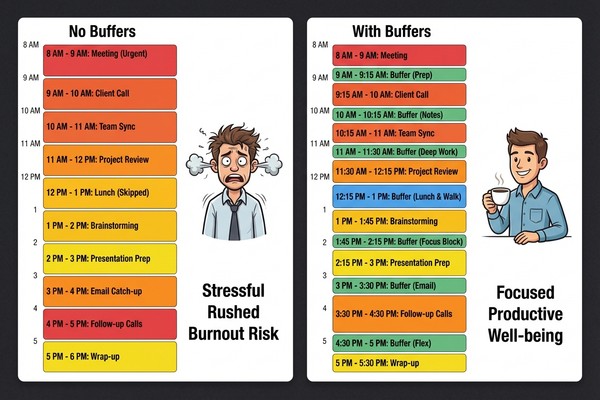

Buffers as Self-Respect

The productivity world has taught us to see buffers as inefficiency, as padding that enables laziness. But buffers aren’t pessimism—they’re dignity. They’re the difference between moving through your day with grace and spending every moment feeling like you’re failing at time management.

Think about it this way: when airlines build buffer time into flight schedules, we don’t call it pessimistic planning. We call it realistic operations management. When engineers design bridges with safety margins, we don’t accuse them of lacking confidence in their calculations. We recognize they’re accounting for real-world conditions.

Your time deserves the same consideration.

A buffer isn’t an admission that you’re slow or inefficient. It’s an acknowledgment that you’re a complex human being operating in an unpredictable world. It’s planning for the reality that sometimes you’ll need to take a phone call, sometimes you’ll hit traffic, sometimes your brain will need five minutes to switch contexts between tasks.

Buffers aren’t about expecting failure—they’re about expecting life.

The Uncertainty Principle for Planning

Here’s a practical approach that’s saved my sanity: instead of asking “How long will this take?” ask “How uncertain am I about this estimate?”

For routine tasks you’ve done many times, add a small buffer—maybe 20%. For tasks with new variables, unfamiliar contexts, or dependencies on other people, add a larger buffer—50% or more. For anything involving technology, children, or bureaucracy, double your estimate and then add a little more for good measure.

This isn’t about becoming a pessimist. It’s about becoming a realist who respects the complexity of execution. When you plan this way, you’ll find something magical happens: you start finishing things early. You arrive places on time. You have moments of calm between tasks instead of constantly rushing.

The goal isn’t to become slower—it’s to become more accurate about what speed actually looks like in your real life.

One Plan, Rebuffered

Right now, think of one thing on your calendar this week that you’ve probably underestimated. Maybe it’s a work presentation you’ve allocated an hour to prepare, or a doctor’s appointment you’ve blocked for exactly the appointment time, or a weekend errand run you’ve optimistically scheduled for two hours.

What would happen if you gave that task the buffer it deserves? What if you planned for the reality that preparation involves gathering materials, that appointments involve parking and waiting rooms, that errands involve traffic and lines and the human tendency to remember three additional things once you’re already out?

This isn’t about lowering your standards or accepting inefficiency. It’s about raising your standards for how you treat yourself in the planning process.

Beyond Individual Willpower

The deeper challenge with planning fallacy is that it reveals the limitations of purely individual solutions to systemic problems. We can get better at estimating our own time, but we’re still operating in a culture that rewards unrealistic optimism and punishes realistic planning.

The meeting that’s scheduled for exactly an hour with no transition time. The deadline that assumes perfect conditions and zero revisions. The family schedule that treats every activity like it exists in a vacuum, unaffected by the chaos of real life.

What if our systems learned from our actual patterns instead of our aspirational ones? What if technology could observe that your “quick grocery run” consistently takes 90 minutes, not 60, and adjust future planning accordingly? What if our tools got smarter about the gap between intention and reality?

This is where the future of planning lies—not in making humans better at prediction, but in creating systems that understand the beautiful, messy complexity of how we actually move through time. Until then, we can start by giving ourselves the gift of honest planning, one buffer at a time.

The planning fallacy isn’t a personal failing—it’s a human feature. But recognizing it is the first step toward planning that actually serves your life instead of setting you up to feel like you’re always behind.

This article was created with collaboration between humans and AI—we hope you ❤️ it.